Between Rose-Colored Rugs and Doomscroll Welfare: Bias, Mood, and What the Herd Actually Tells Us

Between Rose-Colored Rugs and Doomscroll Welfare: Bias, Mood, and What the Herd Actually Tells Us

It struck me on a day when the pasture appeared immaculate. Corners swept clean. Hay arranged with precision. Blankets hanging in a tidy row like ceremonial banners. And there stood a horse, utterly motionless—not visibly suffering, simply suspended, as though the world had paused and forgotten to resume.

In that moment, I recognized how readily my emotional state attempts to author the narrative of well-being. In hopeful moods, I read that stillness as "peaceful." In darker ones, I interpret the identical stillness as "withdrawn." Neither interpretation constitutes genuine attention. They are mental shortcuts—cognitive distortions dressed in equine form. We do this constantly in our own lives too: projecting our inner weather onto circumstances that deserve clearer seeing.

Mood as a Welfare Filter

Our approach to welfare frequently succumbs to an oversimplified formula: suffering equals failure, comfort equals success, full stop. This framework appeals to us because it aligns with our deep human impulse to control outcomes. If we can eliminate every discomfort, we convince ourselves we have fulfilled our duty.

Yet the natural world refuses to operate like a cushioned sanctuary. Some degree of difficulty is essential to cultivating resilience and flexibility. When we compress existence into uninterrupted ease, we do not necessarily foster tranquility—we may instead cultivate brittleness. The horse might appear "low-maintenance" while simultaneously losing the capacity to navigate ordinary circumstances.

The optimistic lens then murmurs: "Look—no conflict. Everything is fine." The pessimistic lens retorts: "Unless it's flawless, it's damaging." Either stance can drive us toward relentless interference, perpetually intervening—until the horse's innate capacities have diminishing opportunities to bear their rightful weight. How often do we do the same to ourselves and those we love—smoothing every path until we've inadvertently weakened the very muscles meant to carry us through difficulty?

The Two Classic Biases in the Barn

Optimism bias frequently manifests as faith in appearances. When food is available, when the enclosure looks orderly, when no visible wounds exist, welfare must surely be adequate. Within this mindset, we can overlook what horses fundamentally need each day: space for locomotion, opportunity to graze, and companionship that allows social structures to flourish.

Pessimism bias emerges as vigilance that refuses to rest. Every indicator transforms into an urgent warning. We perceive routine struggle as evidence that everything is collapsing. This can generate a existence of "remedies" piled upon remedies, until the horse's world requires our perpetual maintenance to hold together.

Neither bias equates to attentive observation. Bias operates hastily. Welfare demands subtlety. The same principle governs our human relationships: quick judgments rarely honor the complexity of another's experience.

What Horses Use Instead of Our Stories

When you observe horses without predetermined conclusions, you begin to notice how much of their equilibrium emerges from quiet negotiations rather than recurring confrontations. The one who defers may shift based on context and circumstance. Decisions about movement can originate from various individuals at various moments. When we impose a singular "leader" framework upon them, we fail to perceive the living truth: bonds that bend and breathe.

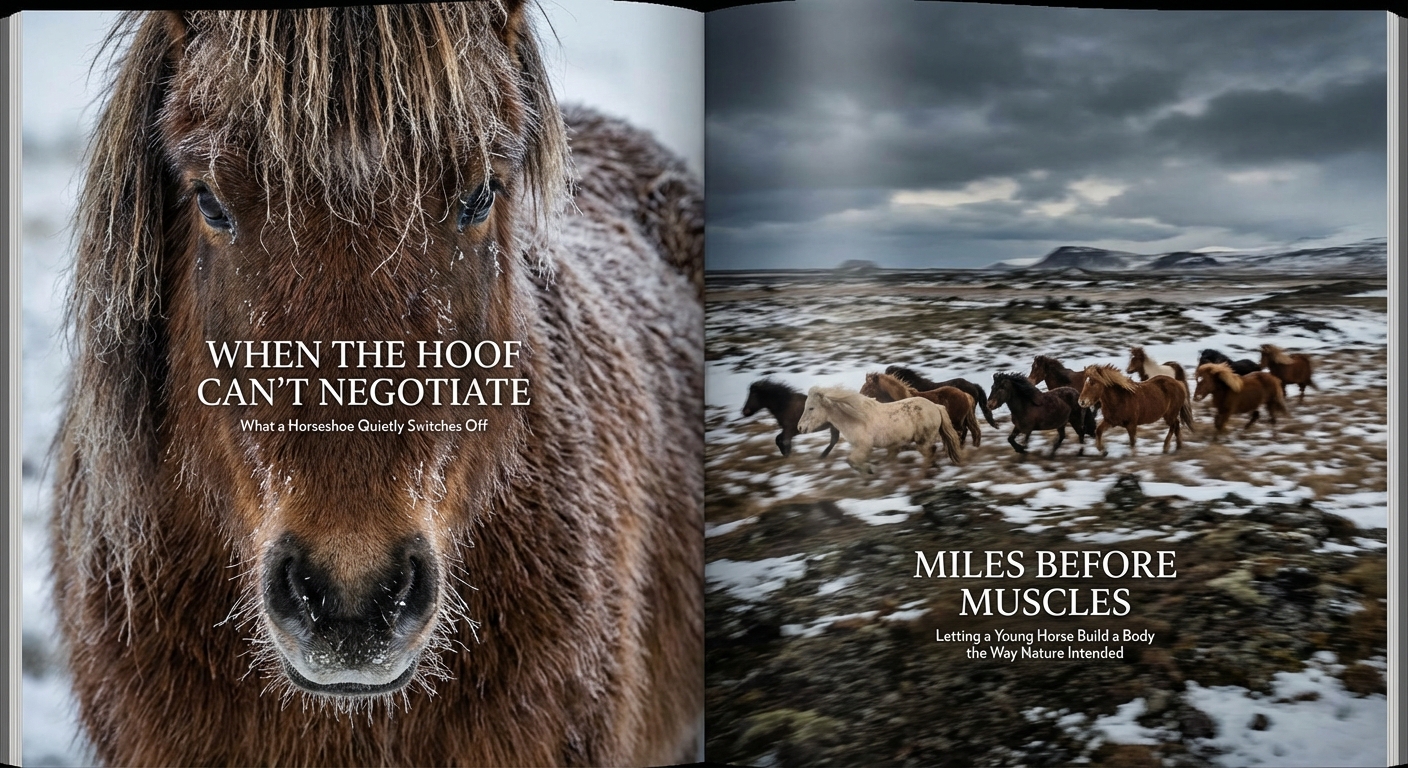

This adaptability holds significance for welfare because it illuminates what horses evolved to accomplish: locomotion, browsing, returning to graze, adjusting proximity, and continuous recalibration. Uninterrupted access to forage sustains the digestive architecture; its absence can invite complications like gastric distress. Repetitive, stereotypic actions are not character defects—they can serve as environmental assessments.

Here is where "neutral nature" becomes actionable: not our engineering of an unblemished utopia, but our cultivation of trust. Not abandonment. Not sentimentality. Trust meaning: offer the horse an existence that can operate on equine principles, then observe what the horse creates within it. Perhaps our own flourishing follows similar logic—less orchestration, more space for our authentic nature to find its rhythm.

A More Honest Coexistence: Trust Without Fantasy

Living alongside horses without riding or training them can still constitute engaged stewardship, simply not the dominating variety.

It might mean emphasizing terrain and duration so the horse can traverse substantial daily distances, rather than converting movement into a human-orchestrated occasion. It might mean establishing grazing as the foundational tempo, instead of manufacturing extended intervals that transform eating into urgency. It might mean embracing social existence as a cornerstone of welfare, acknowledging that group interactions are contextual and that "who displaces whom" does not constitute a fixed identity.

And it might mean attending to the "minor observations" available without cost: does the horse inhabit a body that appears prepared for motion throughout most of its day? Do they oscillate organically between feeding and walking? Do they exhibit repetitive behaviors suggesting their surroundings are too confined, too barren, too fragmented?

There exists also the human dimension: horses reflect our internal climate. When we arrive with anxious correction, we frequently generate additional fragility. When we bring equanimity, cadence, and a calm presence, we tend to establish conditions where trust can emerge—without requiring the horse to earn it through performance. This mirror works both ways: in learning to be steady for them, we often discover how to be steady for ourselves.

Welfare Beyond Optimism and Pessimism

Optimism declares: "All is well." Pessimism insists: "Everything is falling apart." Both represent emotional forecasts.

But the horse engages in something more tangible. The horse is endeavoring to exist: to consume food in harmony with its physiology, to move in ways that preserve its vitality, to belong in ways that settle its nervous system, and to grow through commonplace challenge.

If we aspire to share space meaningfully, we can cease employing our emotional state as the instrument of measurement. We can allow welfare to become a dialogue with what is actually present—one where the horse's requirements for movement, grazing, social connection, and an environment that does not demand perpetual human adjustment are permitted to speak loudest. In this practice lies a template for all our relationships: less projection, more presence; less fixing, more witnessing.

Equine Notion

https://equinenotion.com/