Cortisol as a Concept: Noticing Chronic Stress When the Immune System Has to Share the Same Space

Hook

At dawn, the juxtaposition strikes with an almost unsettling clarity.

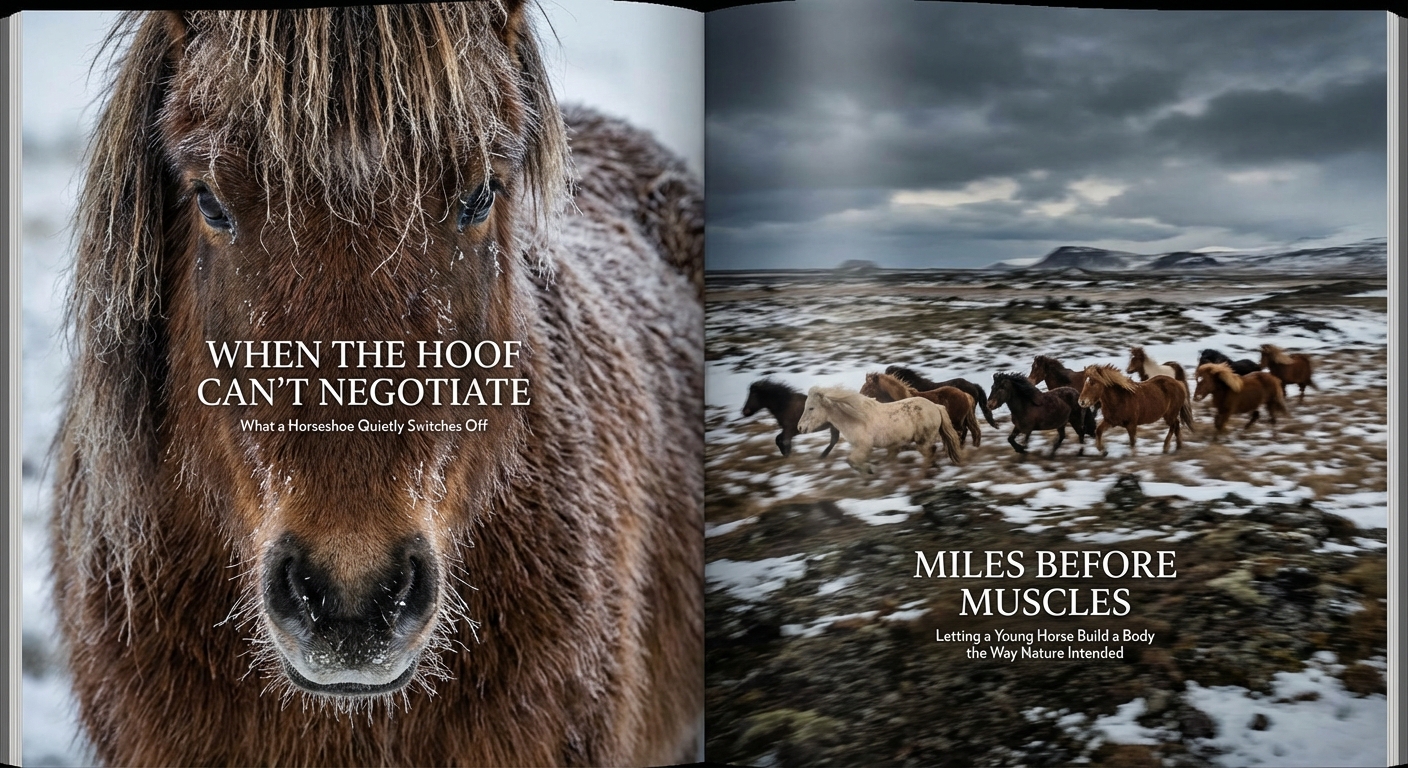

The horses roam across the expanse, navigating their own possibilities—moving between forage, gravitating toward native plants, deciding where to rest. Meanwhile, our dwelling sits enclosed by a boundary that creates the curious impression that we are the creatures contained within a modest pen.

This inversion of perspective carries weight when one contemplates a contemporary term like *cortisol*. Not because measurements are being taken, but because it illuminates a fundamental inquiry about shared existence: what manner of living sustains a quiet hum of tension beneath the surface, and what manner allows a body to descend into stillness—frequently enough, extensively enough, for restoration to find its opening?

We might ask ourselves the same question in our own lives, where the architecture of our days often mirrors the very enclosures we build for others.

1) Chronic stress isn't always loud

Most imagine stress as visible terror or acute alarm. Yet persistent stress can manifest as something far more subdued on the exterior: lingering, expecting, accommodating—repeatedly, day after day.

This explains why confined, restrictive arrangements exact such a toll even when nothing overtly harmful appears to occur. Horses housed in cramped, bounded areas experience a contracted world. Every movement becomes a negotiation against barriers. Options dwindle to near nothing. The creature may continue eating, standing, and resting, yet inhabit a perpetual state of recalibration.

Cortisol, understood this way, functions less as a laboratory metric and more as a reminder: enduring pressure requires no spectacle to be authentic.

How many of us live within invisible walls of our own making—schedules, obligations, digital boundaries—adapting so constantly that we mistake chronic adjustment for normalcy?

2) Space as a daily permission to come down

We granted the horses access to the majority of our property. The outcome borders on ironic: it appears as though we are the ones penned in beside the dwelling.

Yet for these animals, such openness is no mere aesthetic flourish. It transforms the fundamental quality of their existence. With expanded territory, they can drift apart, come together, meander, rest, and determine their own proximities. They need not compress their being into one "appropriate" location.

If persistent stress is, in part, the sensation of being unable to fulfill one's minor choices—where to position oneself, when to proceed, how to withdraw from pressure—then space emerges as a gentle reprieve. Not an initiative. Not a regimen. Simply surroundings that cease posing the relentless question: "How will you conform to this confinement today?"

Perhaps the most radical gift we can offer ourselves is similar: room enough to make small, unscripted choices without justification.

3) Feeding without fixed times: removing the pressure of the clock

Nourishment encompasses more than sustenance; it also embodies temporality.

In our approach to horse care, we avoid feeding on a rigid schedule. Rather, we encourage patterns that mirror natural grazing as closely as possible. This means the day does not fragment into harsh intervals of anticipation and satisfaction. The cyclical tension diminishes—positioning at a gate, watching for the caretaker, orienting the entire nervous system toward an expected occurrence.

This philosophy does not pursue perfection, nor does it romanticize some notion of "wilderness." It represents pragmatic cohabitation: eliminating a recurring rhythm that can silently burden the system with expectancy.

If cortisol serves as your conceptual shorthand for "the body steeling itself for what approaches," then time-bound feeding becomes an ongoing rehearsal of that bracing. When the clock loses its dominion, the waiting loses its grip as well.

We might recognize echoes of this in our own relationship to meals, notifications, and the countless small countdowns that structure our waking hours.

4) Diverse hay and wild herbs: nutrition as self-directed choice

We strive to cultivate an environment where horses encounter various types of hay and uncultivated plants. The intention is not to assemble a selection for human satisfaction. The intention is to allow the horses agency in their choices.

The original observation rings clear: horses possess an innate capacity to select what their bodies require. That single insight contains an entire worldview of mutual existence. Rather than presuming humans must perpetually dictate what the body needs, the surroundings are configured so the horse can engage in its own equilibrium.

When this principle intersects with themes of chronic stress and immune burden, the focus sharpens further: a body under strain gains from fewer confrontations. Not conflicts with herd members, but confrontations with circumstances—deprivation, uniformity, imposed schedules, mandated consumption.

A diverse foraging terrain guarantees nothing. Yet it diminishes the frequency with which a horse must "settle for" what fails to serve.

There is wisdom here for human flourishing: trusting the body's intelligence, offering variety rather than prescription, and stepping back from the impulse to control every intake.

5) Coexistence without riding: the human role as environment, not manager

This reflection concerns dwelling alongside horses without mounting or conditioning them, and that distinction holds significance.

When riding and training disappear from the equation, the inquiry transforms. The bond no longer centers on achievement or obedience. It becomes more elemental: what circumstances do we establish, and what existence emerges within those circumstances?

The positioning of our fence near the residence symbolizes this reorientation. We did not construct a reality demanding the horses conform to our ease at every moment. Instead, we acknowledged that the terrain could genuinely belong to them—and that our human "territory" could be the lesser portion.

This decision transcends sentiment. It is architectural. It marks the distinction between addressing stress once it surfaces and forestalling some of it by declining to generate it.

What might it mean to occupy our human relationships this way—as stewards of conditions rather than managers of outcomes?

6) If cortisol suppresses, then let life support: a simple, grounded takeaway

The framing here employs weighty language—cortisol, immune suppression, chronic stress. The materials informing this piece do not provide clinical explanations, so I will not fabricate them.

Nevertheless, the experiential reasoning remains sound: when stress becomes the baseline condition, the body retains diminished capacity for all else.

Thus the practical response, grounded in what these sources actually offer, is neither a supplement inventory nor a rigid procedure. It is environment and cadence:

- Greater territory accessible to the horses, so daily existence holds authentic possibilities rather than perpetual compression.

- Fewer clock-governed feedings, so the nervous system is not conditioned to spend the day awaiting scheduled relief.

- Availability of varied hay and wild herbs, so the horse can participate in nourishment through instinctive discernment.

Coexistence, understood this way, becomes a form of humility. We cease behaving as though wellbeing is something we "administer to" the horse, and instead construct conditions where the horse encounters fewer occasions to brace.

In the end, this philosophy extends beyond horses to any being in our care—including ourselves. The deepest support we can offer may simply be the removal of unnecessary pressure.

Equine Notion

https://equinenotion.com/