Mud as a Treaty: Letting Horses Wear Their Own Fly Barrier

Mud as a Treaty: Letting Horses Wear Their Own Fly Barrier

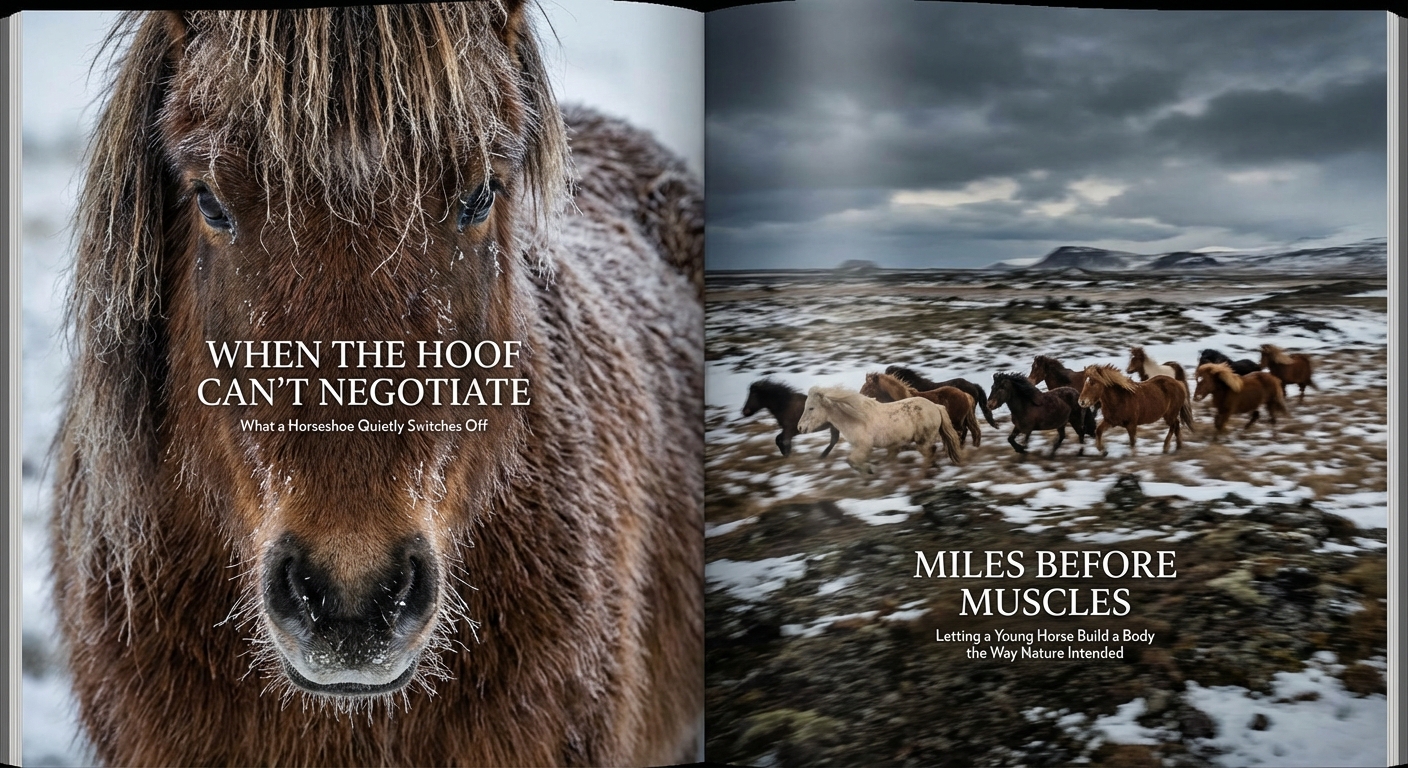

For a brief moment, it appears to be pure disorder.

A horse finds a wet stretch of earth, drops one shoulder, and surrenders fully—lowering themselves to the ground with a conviction we typically save for things we've consciously deemed worthwhile. Limbs tuck beneath, the neck arches and turns, the ribcage sways from side to side. Then comes the opposite flank. Then a deliberate return to standing, as though they've clothed themselves in the terrain.

From a human perspective, mud registers as something requiring correction. Stained blankets. Endless washing. A freshly groomed coat "destroyed" within moments of your careful brushwork. Yet out in the open, that roll may represent the horse selecting a protective covering—a natural barrier of earth that determines what reaches their skin and what does not.

How often do we, too, overlook the wisdom in what appears messy, dismissing nature's solutions in favor of our own manufactured fixes?

A layer, not a lapse

In domestic settings, mud baths are frequently dismissed as an inconvenience, yet the horse approaches them as a valuable tool. This behavior isn't vanity or whim; it's a deliberate choice enacted through their entire being.

When insects populate the daylight hours, the horse does more than simply tolerate them. They respond through locomotion, through strategic positioning, through friction against surfaces, through herd arrangement—and at times, through earth itself. The dried coating transforms into an additional membrane, self-applied without seeking approval from any handler.

This holds significance for partnership beyond formal instruction: it serves as evidence that the horse isn't passively awaiting constant supervision. They are perpetually adjusting their own well-being through whatever their surroundings provide.

We might ask ourselves how often we underestimate others' capacity for self-care, rushing to intervene when patience would reveal their own capable solutions.

The pasture is part of the care

Such earthen bathing requires a landscape that permits it.

The condition of the soil and thoughtful land stewardship are not peripheral concerns; they dictate the range of options available to the horse. When we treat the ground solely as something to maintain in pristine order, we risk eliminating the very surfaces horses rely upon for self-regulation.

Here is where the quiet contributions of functioning ecosystems emerge within equine husbandry. The terrain is not merely scenery for outdoor time—it constitutes a living network capable of enabling countless small, autonomous gestures of self-comfort.

Living alongside horses can mean tempering our instinct to sanitize every space. Not because earth possesses some mystical property, but because when a horse can choose freely among genuine elements—parched ground, canopy cover, moving air, moist soil—they require human intervention and substitutes far less frequently.

Perhaps our own lives flourish similarly when we resist over-engineering our environments and instead trust the organic textures that sustain us.

Movement is the missing half of fly season

A horse with freedom to roam will navigate more challenges independently.

Existence following natural rhythms encompasses considerable travel—a continuous wandering, selecting, foraging, monitoring companions, and relocating. This fundamental mobility serves as more than mere "physical activity"; it represents opportunity. Opportunity to reach the soggy hollow. Opportunity to find the windswept crest. Opportunity to discover the spot where biting insects simply congregate less.

When we confine the horse's territory, we confine their possibilities. As choices diminish, our need to intercede grows.

Even absent any riding or schooling, the decisions we make determine how freely the horse can travel their way toward ease.

The same truth echoes in human experience: when we restrict our own range of motion—literal or metaphorical—we often find ourselves dependent on external remedies for discomforts we might otherwise resolve ourselves.

Relationship shows up at the mud patch

The communal dimension often escapes notice because it unfolds without spectacle.

Who approaches first, who holds back, who claims the nearest position, who defers without confrontation—these are not permanent character stamps branded onto any horse for life. They shift according to the moment, the prize at stake, and the particular bond between individuals.

A muddy gathering place can illuminate this adaptability. What emerges is not a straightforward hierarchy narrative, but rather a fluid exchange—a nearly courteous dance that preserves group harmony without perpetual conflict.

And with sustained observation, another pattern surfaces: the prevailing mood is shaped by recognition and history. Within stable herds, much is resolved through minute calibrations—the angle of an approach, a momentary stillness, a subtle turning aside—rather than outright disputes.

Human communities, too, function best when built on such accumulated familiarity, where small courtesies replace the need for constant negotiation.

Watching mud change the human

There exists a final revelation unrelated to insects altogether.

Mud invites the human to exercise self-control.

It becomes a measure of whether we can permit the horse to remain an animal with their own systems of upkeep. Whether we can exchange our compulsion to govern aesthetics for the subtler labor of cultivating a space genuinely worth inhabiting.

And this returns us to an ancient form of stable wisdom: horses mirror our inner condition. When we arrive wound tight, scrutinizing every smudge and disorder, we establish anxiety as the ambient soundtrack. When we arrive with patience—accepting that comfort may not photograph well—we create space for trust constructed from synchronized presence, a recognized voice, and hours spent watching without ulterior motive.

The earth coating eventually dries. The insects relocate. The horse resumes grazing as though nothing occurred—except that, for a time, they carry the land's own remedy upon their hide.

Equine Notion

https://equinenotion.com/