The Muscle You Don’t Notice Until It’s Gone: How Confinement Shrinks a Horse’s Body, and Space Builds It Back

Hook

Among the most peculiar truths about a horse's form is how silently it transforms.

Not through catastrophe.

Not through an abrupt wound.

Simply through days that mirror one another.

A horse confined to a cramped enclosure need not exert itself. A handful of paces. A few rotations. The identical corners. The same hesitations. And gradually, imperceptibly, the body begins to conform to the dimensions of its existence.

When we granted our horses access to most of our acreage, another truth revealed itself: movement is not an "exercise." It is the invisible architecture of vitality.

We humans might recognize this pattern in ourselves—how the walls we accept, the routines we never question, slowly sculpt us into smaller versions of who we might otherwise become.

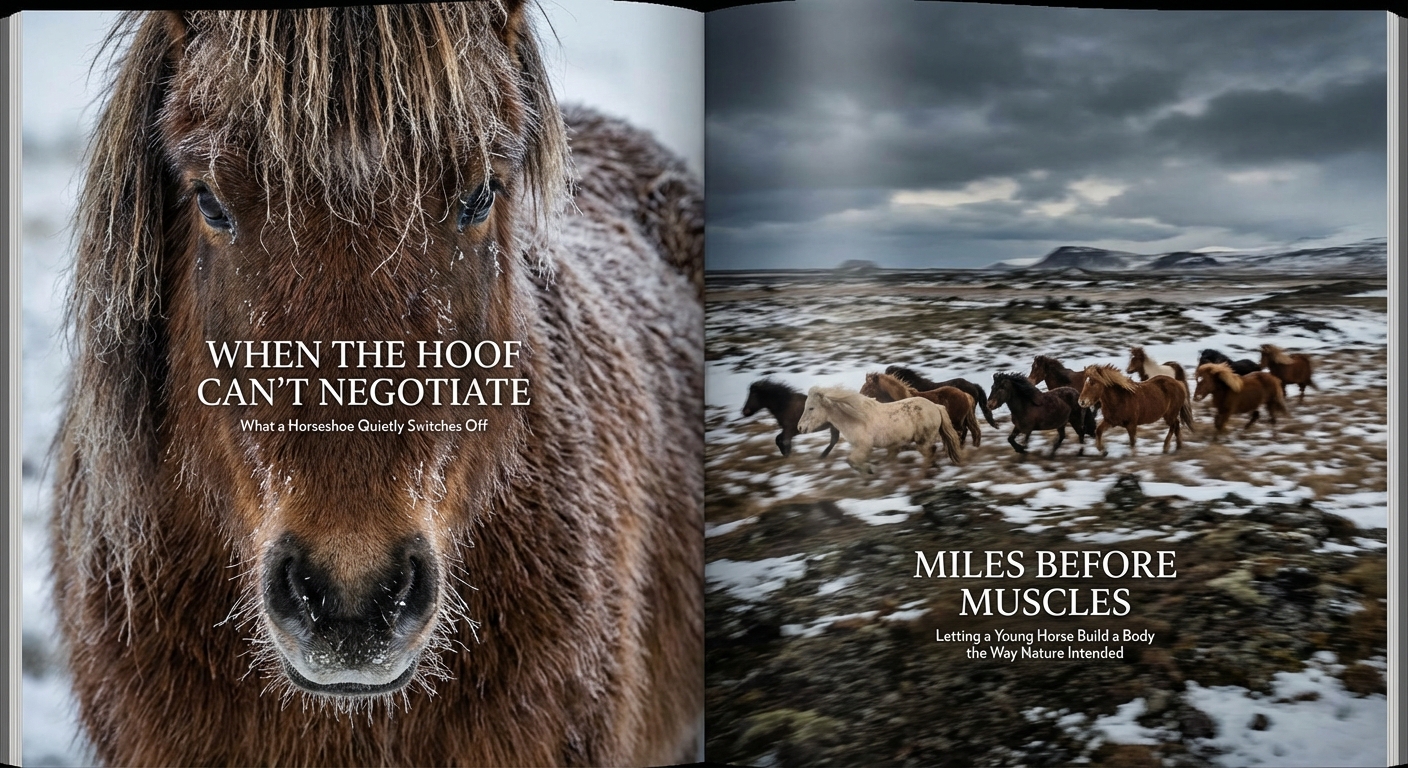

1) When the day is small, the body becomes small

Across countless stables, horses exist within diminutive stalls.

The quarters may be spotless. The schedule may appear well-ordered.

Yet the day remains constricted.

The horse cannot meander. They cannot select a lengthier path simply because something within them desires it. They cannot walk away from an emotion and circle back when ready. They cannot expand the territory between "here" and "there."

Restriction does not merely constrain behavior. It eliminates the ordinary measure of motion that would have unfolded organically, without intention or design.

And when that incidental movement vanishes, the consequence is not purely psychological.

It manifests in the flesh.

A horse's physique is architected around traversing space. When that space is withdrawn, the body must sustain itself in the absence of the very force that naturally sustains it.

How often do we, too, mistake a tidy routine for a full life—only to discover our capacities have quietly atrophied within the boundaries we thought were keeping us safe?

2) The field flips the story: we look enclosed, they look free

When we surrendered the greater portion of our property to the horses, the tableau became almost absurd.

It appeared as though we were the creatures inhabiting the modest fenced plot beside the dwelling.

We erected that barrier, and so it seemed as if we had enclosed ourselves.

That visual paradox carries weight.

It reveals how thoroughly we have normalized confinement for horses: the notion that a vast, locomotive creature can be "managed" by shrinking their universe.

Yet once the terrain lies open, the distinction between being sheltered and being permitted to exist becomes unmistakable.

And you begin to perceive how profoundly a body depends upon the unremarkable act of traveling somewhere.

Not because necessity demands it.

Because possibility allows it.

Perhaps this inversion asks us to examine our own lives: are we designing environments that contain others for our convenience, while believing ourselves to be the generous ones?

3) Movement returns when there is something worth moving for

Open terrain alone beckons motion, yet the everyday incentives to move matter equally.

This is where the approach to feeding transforms everything.

Rather than dispensing food at predetermined hours, we endeavor to nurture instinctive foraging behavior. We cultivate an environment where horses encounter varied hays and uncultivated herbs.

This reshapes the contour of the day.

They do not merely consume.

They seek.

They evaluate.

They decide.

And because choice is distributed throughout the landscape, the horse's body is gently prompted to continue wandering from one curiosity to the next. Not through compulsion. Through the ordinary rhythm of interest.

The outcome is not "training."

It is a day composed of countless modest pilgrimages.

And those pilgrimages are precisely what confinement obliterates.

We might ask ourselves: what small journeys have we eliminated from our own days, and what vitality have we unknowingly forfeited in the process?

4) Muscle is not a project—until we remove the conditions that maintain it

When movement becomes scarce, humans grow tempted to substitute artificial programs for vanished motion.

Yet the deeper inquiry is this: why did orchestration become necessary at all?

In an existence where a horse may wander freely, movement occurs without bargaining.

The horse walks from curiosity. From hunger. From inclination.

They may pause whenever they wish.

They may also continue onward.

Such liberty is not an indulgent supplement. It is the bedrock that prevents the body from contracting into immobility.

Muscular decline under confinement can slip past unnoticed, because it arrives without fanfare.

It makes no announcement.

It merely presents itself as "this is simply how the horse appears."

But when the surroundings shift—when the land unfolds, when the day ceases to be a circuit between walls—you begin to recall what a horse's body resembles when it is genuinely employed.

So too with human bodies and minds: we often accept diminishment as identity, forgetting what we looked like when our lives had room for wandering.

5) Clock-free food supports a clock-free body

Regimented feeding schedules do not merely structure human routines.

They can also collapse a horse's day into anticipation.

We pursue the inverse. We decline to feed according to rigid timetables. We strive for organic foraging.

This is not an ethical performance. It is pragmatic cohabitation.

A horse with perpetual options can navigate the day with greater fluidity.

They are not simply standing idle until the next occasion materializes.

They can persist in making modest choices: some of this hay, then perhaps that herb, then circling back again.

Those choices generate movement that is not contrived.

It is not "labor."

It is existence itself.

And this manner of existing is what the confined horse forfeits most acutely: not one spectacular gallop, but the quiet accumulation of steps that keeps a body vital.

When we structure our own lives around waiting—for the weekend, for retirement, for permission—we too lose the steady rhythm of small choices that keeps us alive in the truest sense.

6) Coexisting means admitting what the environment does to the body

If you dwell alongside horses without mounting them, without schooling them, you nevertheless influence their wellbeing.

Not through what you impose upon them, but through what you permit them to reach.

A cramped stall instructs the body to economize itself.

An expansive stretch of earth tells the body it may continue being a horse.

The transformation is not solely corporeal. It alters the entire character of shared existence.

You cease thinking in "sessions."

You begin thinking in conditions.

Territory.

Accessibility.

Diversity.

Space to wander.

Space to return.

And perhaps the most humbling element is the visual inversion: in a life where horses occupy most of the land, it can appear as though humans are the ones behind the barrier.

That image preserves the question's integrity.

Who is being restricted for whose ease?

And what does that restriction silently extract from the body across time?

The honest reckoning extends beyond horses: every environment we create—for others, for ourselves—is quietly shaping bodies and spirits in ways we may not notice until something essential has already disappeared.

Equine Notion

https://equinenotion.com/