The Stall as a Machine: How Confinement Turns Horses Into Ongoing Projects

The Stall as a Machine: How Confinement Turns Horses Into Ongoing Projects

What do we truly construct when we erect a stall—a sanctuary of rest, or an apparatus demanding our constant intervention to prevent its collapse?

I recall moving along a corridor of enclosures and catching the same rhythm over and over: a hoof striking, then silence, then another strike. Not especially loud. Nothing theatrical. Simply repetitive, like a metronome left running indefinitely. The horse was not acting out. There was nothing in its behavior that suggested playful defiance. It appeared to be a body attempting to complete an action it could never quite fulfill: to walk, to browse, to wander toward a companion, to pause, to drop the head, to begin once more. How often do we, too, find ourselves caught in loops of incomplete gestures—reaching for connection, meaning, or movement that our circumstances will not permit?

Within these walls, we assume the role of what the open world would naturally provide without demand. We dictate feeding times. We orchestrate companionship. We prescribe motion. We determine when darkness falls and when morning arrives. And yet we express astonishment when the horse begins devising its own methods to occupy the hours, or when anxiety manifests as a seemingly meaningless repetitive behavior—until we recognize it as a signal: some fundamental need remains unmet. Perhaps we should ask ourselves how many of our own strange habits are signals we have learned to ignore.

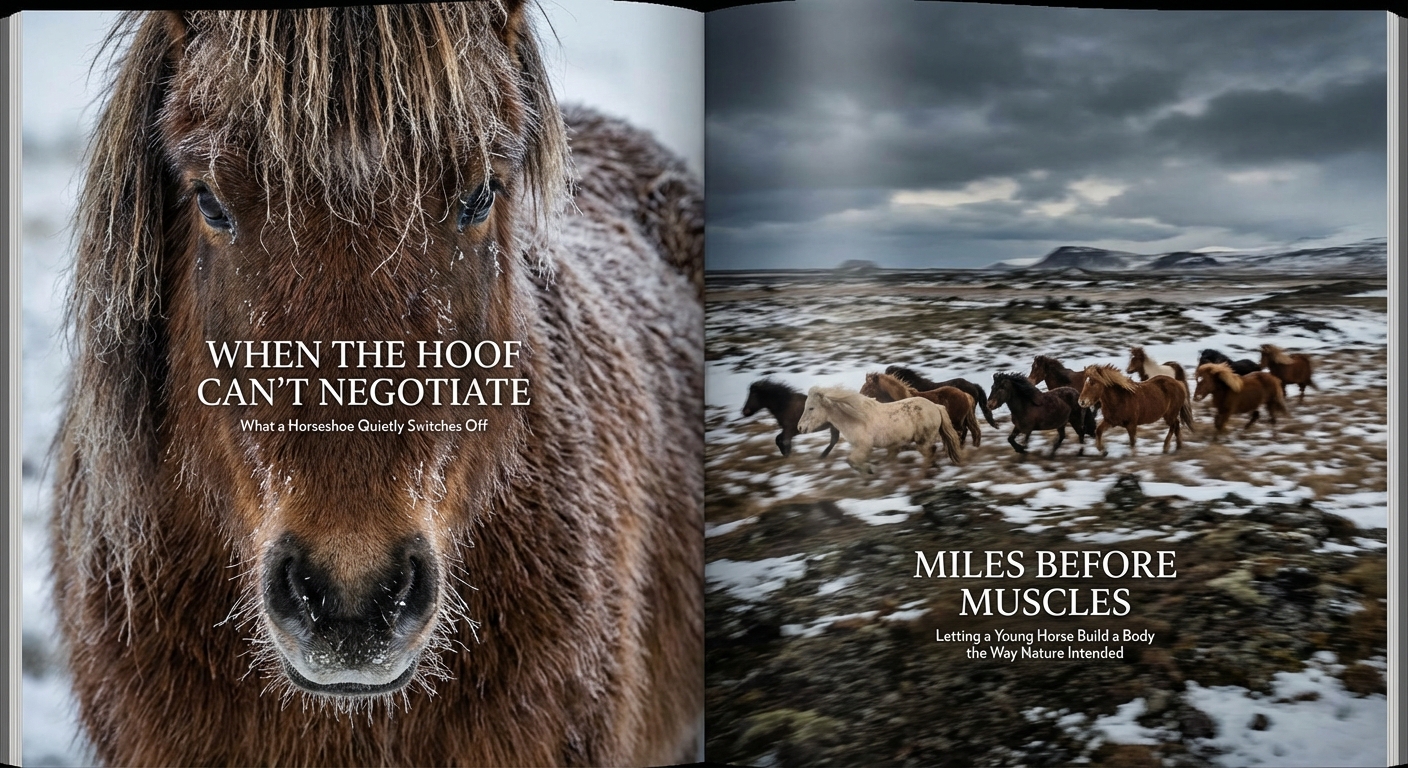

Among the most peculiar aspects is how rapidly the interventions proliferate. The stall generates an absence, and that absence demands administration. The horse ceases eating for extended periods, and suddenly every choice becomes governed by urgency—for the digestive system does not accommodate our timetables. The horse cannot traverse its territory, so we attempt to offset this with modest substitutes. The horse cannot negotiate space and bonds according to its own instincts, so we curate its social existence as though consulting an agenda. We might recognize this pattern in our own lives: the more we control, the more there is to manage.

Within a more organic cadence, so much of this upkeep dissolves into the fabric of existence. Grazing is not an occasion; it is the foundation. Locomotion is not exercise; it is the substance of the day itself. Rest need not be imposed; it emerges naturally when the body has finished wandering and feeding. Even the curious, deliberate behaviors horses exhibit—seeking out mud, selecting particular plants, treating the landscape as a living apothecary—demand access to a world that extends beyond four confining walls. There is wisdom here for us: that wellbeing often requires not more intervention, but more space.

When we stable a horse, we do not merely shelter an animal. We inherit a vocation: to sustain a life that would otherwise sustain itself.

Equine Notion

https://equinenotion.com/