When Calm Is a Shutdown: Reading HPA Strain in the “Good” Horse

The Misread Quiet

There exists a particular stillness that humans instinctively praise. The horse remains motionless in the stall, utters no call, offers no pawing, voices no objection. We call it courteous, well-mannered, uncomplicated. We construct an entire mythology around how "good" this animal is.

Yet prolonged stress leaves its own signature, and it is not always audible.

When horses live in isolation, cortisol—the hormone of stress—rises. Simultaneously, oxytocin—the hormone of connection—falls. This pairing is significant. It suggests a tension that transcends momentary discomfort, pointing instead to a sustained, erosive discord between a social creature's fundamental needs and the existence we have constructed for them. When this discord persists, behavior may compress into something humans wrongly celebrate: the shutdown that masquerades as tranquility.

Here is where the concept of learned helplessness transforms our understanding. A horse may seem "fine" precisely because it has ceased to anticipate that its world will respond.

How often do we, too, mistake our own quiet for peace—when silence is merely the sound of having given up on being heard?

The Body That Can't Finish the Stress Cycle

A stress response is not inherently problematic. Nature's design includes minor hazards and modest challenges; these are features, not flaws. The difficulty arises when the horse cannot bring to completion what the stress response is attempting to accomplish.

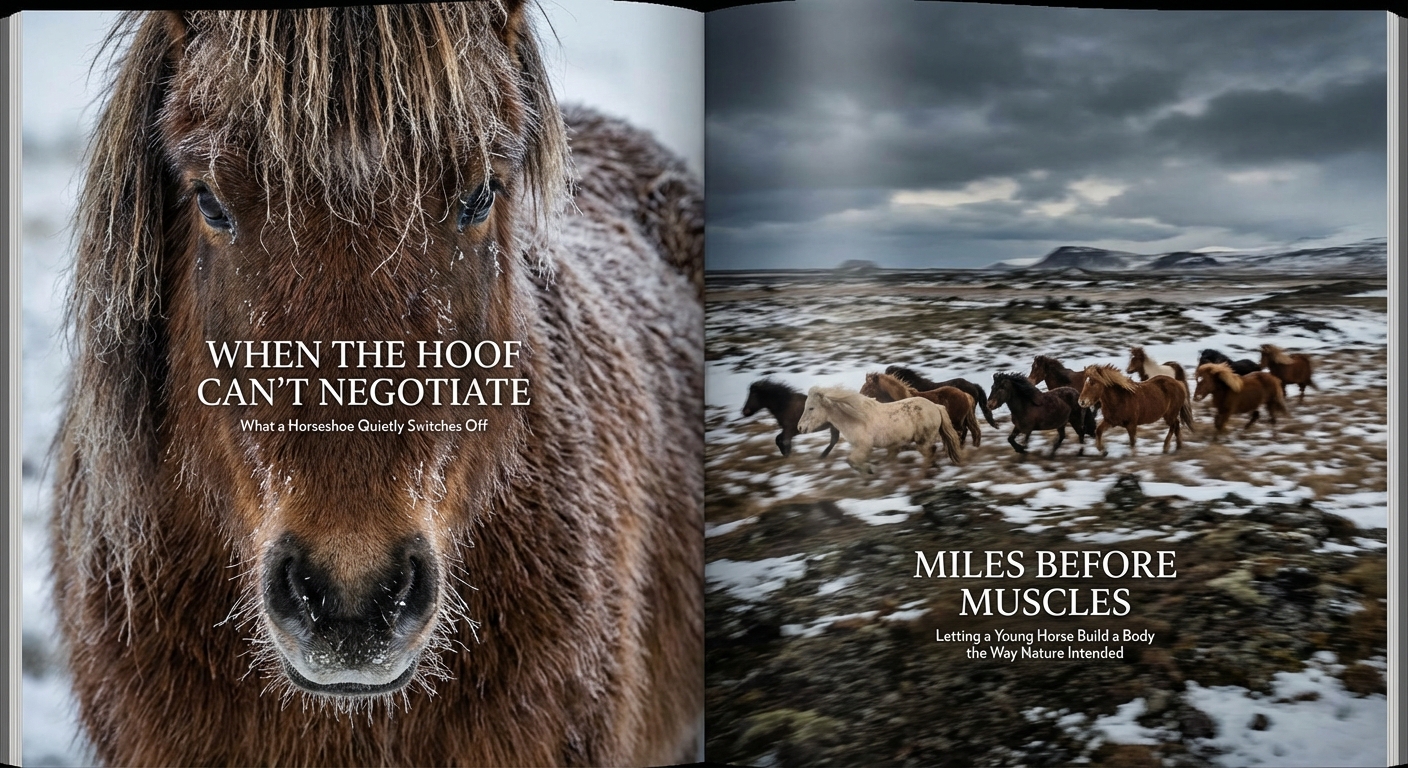

Across a living terrain, horses remain in motion—frequently traversing a daily range of 15–30 kilometers—while eating in an unbroken cadence. They also sustain proximity to other horses. These three elements—locomotion, perpetual foraging, and social bonds—are not indulgences. They constitute the body's pathway home.

When a horse is enclosed, nourished on a timetable that creates vast empty intervals, and severed from authentic companionship, the stress response finds no outlet. The system continues receiving "pause" commands. Cortisol remains elevated. Eventually, this ceases to be mere stress—it becomes erosion.

Humans frequently react by intensifying their control over the horse, because the horse's needs begin to appear as "problems." Yet many stereotypic behaviors—such as weaving or cribbing—are more accurately understood as environmental signals. They are not character defects; they represent a horse attempting to self-soothe when the environment refuses to provide regulation.

We might recognize this pattern in our own lives: how often do we pathologize someone's coping mechanisms rather than questioning the conditions that made them necessary?

Herd Life Is Not a Single Boss—It's Many Small Agreements

Humans are drawn to tidy social narratives: one dominant horse, everyone else falling into rank. But communal existence is typically far more nuanced.

Who defers can shift according to what is at issue—territory, nourishment, rest, proximity. Who initiates movement may also vary. Choices can be distributed among individuals and across moments.

What bearing does this have on chronic cortisol and HPA strain?

When we misinterpret herd dynamics, we sometimes eliminate the very element that keeps horses regulated: adaptable social existence. We separate horses "to avoid conflict," we cycle turnout in patterns that unsettle relationships, or we maintain isolation because it appears more secure and convenient.

Yet collective equilibrium frequently emerges from repeated, gentle negotiations—brief hesitations, angles of posture, decisions to withdraw. These moments constitute regulation in action. They are the equine equivalent of releasing breath. When social existence is reduced to bars, partitions, and fleeting supervised encounters, the body forfeits a primary instrument for calming itself.

Human communities thrive on similar currencies—the small yieldings, the unspoken accommodations, the daily micro-agreements that weave belonging without anyone declaring dominance.

Coexistence as an HPA-Friendly Lifestyle

Coexistence apart from riding or training can still constitute engaged, purposeful stewardship. It is not inaction. It is selecting a life that renders "calm" genuine rather than manufactured.

Several principles emerge directly from what we already understand:

- Prioritize social contact. Isolation drives cortisol upward and bonding chemistry downward. Social architecture is a welfare necessity, not an optional enhancement.

- Protect the long chew. Uninterrupted foraging sustains digestive comfort and helps forestall ulcers. The grazing body anticipates food as a continuous backdrop, not as an occasion followed by emptiness.

- Honor movement as baseline, not exercise. A horse evolved to travel 15–30 kilometers daily does not move solely for athletic purpose. Movement is integral to how the system maintains equilibrium.

- Read stereotypies as information. Stabled horses are 5 to 10 times more prone to developing stereotypic behaviors. Should these behaviors emerge, it is worth receiving them as communications about the environment, not misconduct to extinguish.

Here, too, a human's interior state carries more weight than we prefer to acknowledge. Horses reflect what we bring into their presence. Turbulence in the human often generates distance; serene invitation can draw a horse nearer. When coexistence is founded on mutual rhythm—unhurried breath, unwavering presence—synchronization becomes possible. This is not "training." It is the nervous system perceiving safety close at hand.

Perhaps the deepest gift of living alongside horses is this mirror they hold: an invitation to examine what we carry, and whether our own nervous systems have found their way back to ground.

The Ethical Shift: From Obedience to Conditions

If chronic cortisol elevation and HPA strain can conceal themselves within a compliant exterior, then "good behavior" ceases to function as a dependable welfare measure.

The ethical inquiry shifts from how tractable the horse is to what circumstances the horse inhabits.

Nature does not abolish difficulty; it ensures difficulty does not become inescapable. A horse encounters modest obstacles and then returns to the herd, the forage, the motion. That return is everything.

When we architect a life that eliminates the return—no genuine social bonds, no continuous foraging rhythm, no substantive movement—we should not be astonished if the horse's body settles into a prolonged stress state. And we should not mistake the absence of protest for the presence of peace.

Coexistence invites a different form of pride: not "my horse never causes trouble," but "my horse has space to exist as a horse—and need not vanish into themselves merely to survive another day."

This reframing extends beyond the paddock. In every relationship, in every institution, we might ask: are we measuring success by silence, or by the conditions that make flourishing possible?

Equine Notion

https://equinenotion.com/